Intentional Creations

In an imposing Croatian dormitory, one reminiscent of a government building in its grandeur and implied menace, Andy Dwonch (’99) played chess with a paralyzed Bosnian refugee named Ned.

Dwonch, between his fourth and fifth year at Gonzaga University, was spending summer 1998 in Croatia living and working in a refugee camp full of Bosnians who had fled the violence and horror of a civil war.

A kid from Walla Walla, he’d already gotten a taste for international travel and aid work as a junior studying in Florence.

But the civil engineering student experienced something new while in Croatia partaking in the daily existence of the uprooted. And much of that experience revolved around Ned.

A car accident had left Ned paralyzed from the neck down. But he spoke English and played chess, two things Dwonch knew something about. They struck up a friendship.

“He couldn’t move the pieces, but he would basically tell me the moves to make for him,” Dwonch said. “The entire summer I played him every day and I never beat him once.”

And then, Dwonch left and returned to Gonzaga. Returned to his life in the United States.

Ned stayed behind.

“A few years later Ned died living in the same camp,” Dwonch said. “It left a bitter taste knowing our impact was significant day-to-day, but it wasn’t lasting or change-making.”

He added, “It made me want to find a way to be an agent for change. I was on the verge of having my engineering degree. I thought about ways I could use it to build schools or shelters or those sorts of things. Ways that I could use my engineering knowledge to make a difference for people like Ned.”

As a graduate of Gonzaga’s School of Engineering & Applied Science (SEAS), Dwonch was well-suited to contribute to such structural designs and improvements.

“I really decided that I wanted to use my engineering skills to make a difference in people’s lives,” he said in a Skype interview from Palestine.

Fast-forward 20 years.

Dwonch is the mission director in Palestine for Mercy Corps. It’s one of the many international aid jobs he’s held in the 19 years since he graduated from Gonzaga.

His experience in a Bosnian refugee camp has reverberated outward, shaping and forming his life’s work. Although he’s not a working engineer, the technical skills he learned at Gonzaga serve him daily.

For instance: In the Gaza Strip he’s worked on a project to provide clean and safe drinking water. Currently 95 percent of the groundwater in Gaza is polluted, a salty soup unfit for consumption. Dwonch’s job? Coordinating among various private companies, governments and cultures.

“Again, I’m not the technical project manager but I’m helping to support the technical team and supporting on political issues,” he said. “There are a lot of complexities that have to be addressed in order to make that happen.”

Eventually, he said, “this project will provide a long-term sustainable solution for people to get drinking water that is clean and is safe.”

That kind of ethic, one combining the technical rigor of an engineering education with the humanistic focus of Gonzaga’s undergraduate core, is exactly what SEAS faculty and staff who helped form Dwonch’s education were striving to create.

Whether it’s international aid work, designing a state-of-the-art pathogen center or helping improve communication between production workers and engineers, most Gonzaga graduates are animated by the same underlying humanistic ethic.

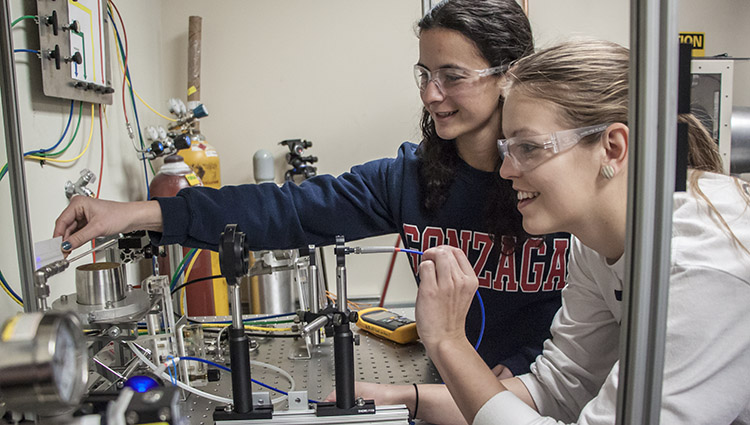

Mechanical engineering students set up Dr. Marc Baumgardner's engines lab with a laser ignition system in 2018.

Miranda Myers (’15) didn’t know what she was doing when she first came to Gonzaga.

Myers grew up in Whitefish, Montana. A town of less than 8,000.

“I didn’t even know what an engineer was,” she said of her first year at Gonzaga.

In high school Myers enjoyed math, but she didn’t want to be a math major.

“I didn’t really get much exposure to anything outside the very typical subjects,” she said. “I was very good at school, but I didn’t have one thing there that I really liked.”

A bit adrift her freshman year she started to hear about the engineering program from friends. Specifically, computer engineering. It sounded interesting and involved math. So, in her sophomore year she signed up. But, she was behind.

“When I took my first computer science class I was so lost,” she said. “I did not have a clue what was going on.”

Myers wasn’t about to give up. Instead she started looking for help.

“I went to Professor Paul De Palma’s office every single week and he helped me with pretty much every assignment,” she said. “He was really patient and really nice and really supportive of me.”

That support ignited something. After her sophomore year she interned at the NASA Glenn Research Center and then at the NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

Now, working as a software engineer at the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory, Myers works with the U.S. government. She can’t talk in detail about what she does, but she is the technical lead of her team, overseeing six people doing back-end development for scientific applications.

“The computer science program gave me the skills to be able to be very successful at a nationally recognized engineering company,” she said of her time at Gonzaga.

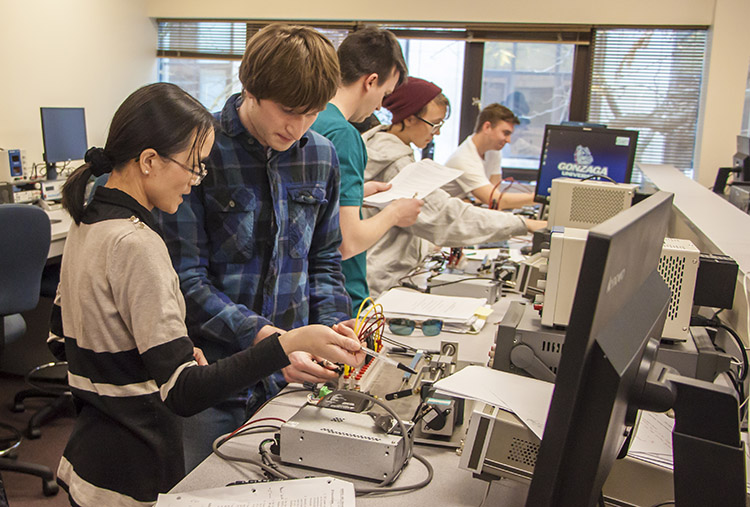

Electrical engineering students work with Dr. Meirong "Mary" Zheng in 2018.

For Anthony Schoen (’12), the value of his Gonzaga engineering degree is just beginning to come into focus.

Schoen, a principal at MW Consulting Engineers in Spokane, works in HVAC (heating, ventilation and air conditioning) design and is an adviser of student teams within the senior design program. He focuses primarily on health care HVAC systems, a job, he said, he never imagined doing, much less enjoying as a student at Gonzaga.

“If you’d asked me, ‘What do you want to do?’ the list was huge,” Schoen said. “If you’d asked me, ‘What would I not want to do?’ It would have been HVAC design.”

But he’s found HVAC design to be challenging, varied and rewarding.

For instance, in 2016, just four years out of college, he was asked to tackle a complex and pioneering health care problem.

Design an HVAC system for the wing of a hospital that is completely separate from the wider HVAC system. Why? To keep deadly viruses contained.

And so, Schoen helped design Providence Sacred Heart Medical Center’s “special pathogens unit.” The completely contained hospital ward is designed to isolate and treat patients with highly infectious diseases. Think Ebola, although the next epidemic likely won’t be that.

Schoen is immersed in the details of the project. But in the same way that Dwonch has to learn and connect people from different social backgrounds and cultures, Schoen had to delve deep into the world of infectious disease. He spent weeks reading and talking to experts.

All, of course, while simultaneously working hand-in-hand with other engineers, the hospital, the regulatory agencies and scientists.

At that time there were no comparable units in the United States.

“We had to be very creative,” he said, “while completely keeping the public and patient safety in mind.”

And Schoen did it. The unit is up and running and a number of mock drills have been conducted in a facility that he is partially responsible for creating.

Schoen credits his success, both in that project and more broadly as an engineer, to his time at Gonzaga. And, he said, as he’s learned more about the professional engineering world he sees clearly Gonzaga’s impact.

“The people leaving Gonzaga, I would say 90 percent of them are atypical engineers,” he said. “They can communicate, and they are good in social environments, but they are also technically trained.”

(Shown here: Ryan Kellogg ('14), mechanical engineer at Space X; Mareval Ortiz-Camacho ('18), electrical EIT at HDR; Anthony Schoen ('12), mechanical engineer at MW Consulting)

An annual computer-based ethics training is one of the ways Roy Wortman (’01) is reminded of his Gonzaga education.

“It’s always struck me as kind of silly that sitting in front of a computer and clicking buttons will make you ethical,” he said.

Wortman said his time at Gonzaga ingrained a sense of ethics, one hammered out in philosophical debates and English class discussions. Pair that with the technical training he received as a mechanical engineering student and Wortman said he’s well-suited for his job at UTC Aerospace Systems in Spokane.

As a quality control engineer he is tasked with troubleshooting production and design issues with the carbon brakes UTC Aerospace produces for Boeing and others. When there is an issue, Wortman communicates between the engineers and the production staff.

“I would say the biggest impact Gonzaga had was teaching me the importance of building trust in both technical and personal relationships to accomplish goals,” he said. “Having that heart and mind, having that whole-person experience at Gonzaga really helped.”

In particular, Wortman credits Gonzaga’s senior design program for marrying his rigorous technical know-how with the softer people skills.

The senior design program is a major reason that Gonzaga graduates “atypical” engineers.

The value of the program lies in the hands-on experience provided to engineering students who likely have never worked professionally before.

“It’s the first time most of our students have worked in a team for nine months on a project,” said Toni Boggan (M.A. ’11), the academic director of engineering design and entrepreneurship. “It enhances their teamwork skills. It’s the first time they’ve had a chance to use all of the skills they’ve learned so far.”

Boggan has worked with senior design projects for a decade at Gonzaga. When she started, there were about 100 seniors doing 25 projects. In the 2018-19 school year there are 220 seniors and 60 projects.

“They’ve had a lot of experience working on things by themselves,” she said. “Now they have to work in a team and they have to communicate their work. It’s really good for them to learn how to impart technical knowledge to a nontechnical audience.”

She added, “If they can’t explain it, it’s never going to work.”

Alums like Andy Dwonch, Miranda Myers, Anthony Schoen and Roy Wortman don’t tumble fully formed out of an academic void.

No. They have been intentionally created by the Gonzaga School of Engineering and Applied Science’s clearly articulated vision.

“We want our engineers to understand what a biologist understands. To understand what an anthropologist understands. To be able to use journalism skills,” said Stephen Silliman, former dean of SEAS. “[They] need a broad skill set in addition to their technical training.”

And while SEAS has been doing that for decades, plans currently in the works will only further that mission. The Integrated Science and Engineering building, while still in the conceptual phases, would give engineers, biologists, journalists and more a shared space in which they could work and learn together.

“We have a vision for the engineering and computer science disciplines to really fully integrate with the natural science disciplines and with some of the others, like humanities,” Silliman said, just prior to taking a professional leave to collaborate on development projects in Benin, West Africa.

Joseph Fedock, the interim dean of SEAS, shares that vision. In fact, the former administrator at Montana State University and faculty member of Santa Clara University’s engineering school, has personal experience with the power of what a broad engineering education can do.

He recently discovered that a former student studying civil engineering has risen high within the ranks of the Jesuits. The priest isn’t using his civil engineering degree. But he is using the analytical, problem-solving framework he learned in a Jesuit engineering program.

“I think that is really cool,” Fedock said. “That someone could utilize their technical skills and their technical background. It’s the problem-solving mentality and that is where engineers and computer scientists excel.”

You can have an impact on farmers affected by drought.

You can have an impact on farmers affected by drought.

Erik Allen (’19, civil engineering), a fifth-generation farmer, wants to use his Gonzaga education to solve agricultural problems. The new Integrated Science and Engineering facility will give students like him the Jesuit-inspired opportunities to put their innovative ideas, expertise and hearts for others to work and change the world.

Your impact starts now. Visit gonzaga.edu/ReadersCare to learn how.

Read more alumni stories here.

Read more alumni stories here.

- Academics

- Alumni

- Careers & Outcomes

- School of Engineering & Applied Sciences

- Electrical Engineering

- Mechanical Engineering

- Civil Engineering

- Computer Engineering

- Gonzaga Magazine