On History, Myth, and Popular Memory of the Nineteenth Amendment

“The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex.”

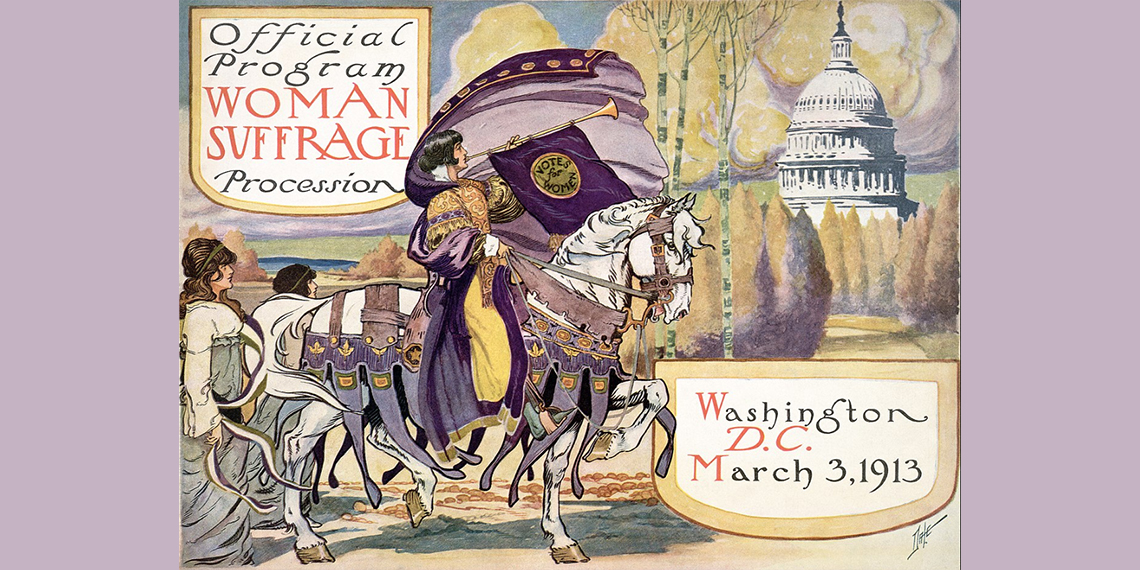

In August 1920, the thirty-sixth state approved the Nineteenth Amendment which resulted in its ratification and addition to the U.S. Constitution. The Nineteenth Amendment guaranteed that the civil right to vote could not be “denied or abridged” based on sex.

Today, as we mark a century since the ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment, many Americans are inclined to give undue credit to the Amendment and undue criticism to those who worked for its passage. The Nineteenth Amendment was a great achievement but also a limited one. At the same time, its supporters included a much broader group of activists than many Americans remember.

Safeguard for Women’s Votes

The Nineteenth Amendment protected the right to vote for women citizens. This was significant because states had granted and then rescinded voting rights to women since the founding of the Republic. Early in the 19th century, some states took away women’s voting rights because lawmakers decided women were not sufficiently independent to perform the important task of voting. Decades later women and men organized in favor of “woman suffrage.” State legislatures responded in a variety of ways: some states allowed women to vote only in local school board elections, some allowed women to vote in primaries or on tax levies, others allowed women to vote for state lawmakers, and some states slowly granted them full voting rights in all elections. Still other states adamantly opposed granting women any voting rights.By 1900, the forty-five states that made up the United States had a baffling array of voting rights for women. Four states had granted partial voting rights, nineteen allowed women to vote just in school elections, and two states defeated woman suffrage measures that year. Only four states had granted women full voting rights, but that number grew to twenty by 1920 when the Nineteenth was ratified. This shows us the upsurge in popular support for the right of women to vote. When Americans ratified this Amendment, they expanded the voting rights of women in eighteen states, and granted the first voting rights to women living in seven of those states!

Which Women Got to Vote?

The Nineteenth Amendment granted all women citizens, equally, the right to vote. The Amendment doesn’t specify the race of voters; it specifies that sex cannot be used to deny the right to vote.

Today, some Americans assume that woman suffrage extended only to white women, but this wasn’t the case. This common misperception of women’s suffrage is due, in part, to popular women’s histories of the 1970s and to assumptions about voting

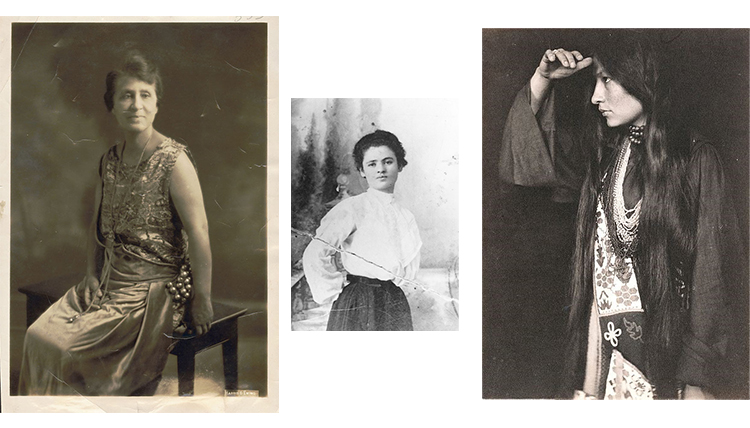

The myth of white-only women's suffrage is the result of biased sources and celebratory, popular histories. White suffragists from the early 20th century wrote memoires about the suffrage movement where they extolled their efforts and those of other white women in securing the Nineteenth Amendment. They excluded or downplayed the efforts of women of color, of immigrant women, and of working-class women. In the 1960s and 1970s, American women worked to recover their history and they used these biased sources. Their stories of women’s suffrage focused almost exclusively on native-born, white, Protestant, middle-class women. These popular histories overlooked the important work of women of color, working-class women, some white women (like Catholic women), and immigrant women (some of whom could not vote but who campaigned anyway). Historians, though, have documented the stories of all these women.

What those stories tell us is that women of color campaigned tirelessly for suffrage and, after 1920, they voted throughout the United States. When American women went to the polls in the fall of 1920, they included Chinese American Tye Leung Schultz in California, African American Mary Church Turrell in Maryland, and, in New York State, disabled American Helen Keller, white middle-class socialist Florence Kelley and naturalized Jewish immigrant Clara Lemlich.

What surprises many Americans is that even Black women in parts of the Jim-Crow South voted in 1920, and they did this in the face of violence and intimidation by white Southerners who sought to disfranchise Black men. (This same violence eventually eroded the rights of Black women to vote, but Black women and men joined crusades to regain their voting rights.)

(Above, left to right: Mary Church Terrell, African American activist for civil rights and suffrage; Clara Lemlich, an immigrant and labor rights leader; and Zikála- Šá (Gertrude Bonnin), a Lakota Sioux who advanced women's suffrage. All photos public domain.)

These examples of disfranchisement remind us that states determine who gets to vote, and constitutional amendments merely detail restrictions that states cannot enforce. (To date, those Amendments ban restrictions based on race, color, previous condition of servitude, sex, failure to pay a poll tax or any other tax, and age.) Many Americans are familiar with the ways states circumvented constitutional mandates. States invented literacy tests and poll taxes and implemented them throughout the U.S. They restrict the voting of African Americans, Mexican Americans, and Indigenous Americans. Not every state had these laws and not every state enforced them in the same way (or against the same racial or ethnic group). Some states—like Washington State—did not have de jure suffrage discrimination. But those states that did, in the South, in California, Idaho, and South Dakota, eventually faced national scrutiny. When Congress passed the 1965 Voting Rights Act, these had to abandon voter suppression laws.

Enduring Restrictions on Voting

Despite the achievement of the Nineteenth Amendment not all Americans enjoyed the right to vote in 1920. This right extended only to citizens and only to those living in U.S. states or territories.Not all Native Americans were citizens. So, in 1920, some Indigenous women could not vote. Nevertheless, Indigenous women activists worked in favor of suffrage because they realized the significance voting could have in their communities. (In 1924 an act of Congress compulsorily naturalized all Native non-citizens.)

Women who lived in U.S. colonies also didn’t gain the right to vote. Some constitutional protects did not extend to citizens living in colonies like Puerto Rico, Guam, the Philippines, the Virgin Islands, and American Samoa. Women in Puerto Rico, for example, finally won the right to vote in 1929, but even today Puerto Ricans (all of whom are U.S. citizens) do not elect any representatives to Congress and they do not get to vote in national, presidential elections.

In 1920, certain immigrant women could not vote because the U.S. barred them from naturalizing as U.S. citizens. This was the case for women (and men) who were born in China, Japan, the Philippines, South Asia, Southeast Asia, and Polynesia. Not until 1943 did Congress began to overturn these race-based prohibitions on naturalization. Long-time residents and newly naturalized citizens voted as soon as they were eligible.

Finally, we should not assume that voter restriction is a thing of the past. Voting remains a significant and powerful part of our democracy and, for that reason, voting remains a matter that states and political group want to define or redefine.

Many states, for example, prohibit people convicted of felonies from voting. Some states disfranchise them for life, even after they have completed their sentence. (And felonies can include horrible crimes as well as, in some states, possession of cannabis, “sodomy,” forgery, and the theft of trademarks). In 2013, the Supreme Court nullified an important piece of the 1965 Voting Rights Act. Since then dozens of states have passed new laws restricting citizens’ access to voting by requiring specific photo I.D., by reduced early voting, by limiting the number of polling places, and by reduced the ease of voter registration.

So, Does the Nineteenth Amendment Matter?

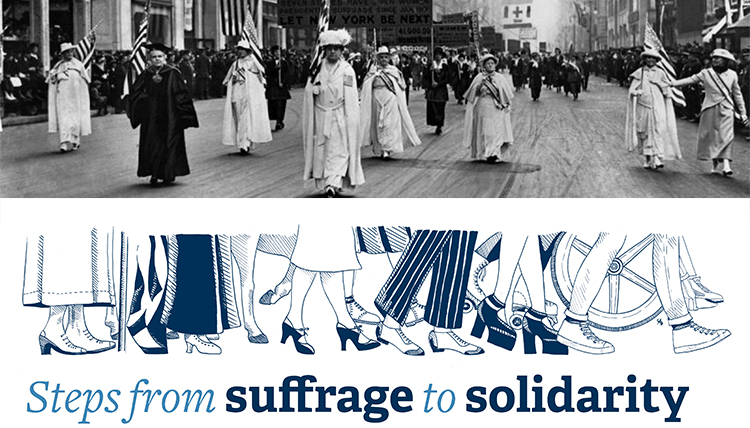

Do you know how people register to vote in your home state? Do you know what is required to vote? If not, find out, and consider how these regulations shape the voting population of your hometown, your region, and your state. More than a century ago, American women asked the same questions and decided that suffrage inequality limited their political power, undermined their rights, and contradicted American democracy. American women fought for voting rights and they achieved a crucial milestone in 1920. But the Nineteenth Amendment did not end all civic inequalities, and their struggle didn’t end in 1920. So, women activists persisted throughout the 20th century and even to the present day.

Veta Schlimgen, Ph.D., Associate Professor of History

Gonzaga University College of Arts & Sciences

For Further Reading:

- Glenda Gilmore, Gender & Jim Crow: Women and the Politics of White Supremacy in North Carolina, 1896-1920 (University of North Carolina Press, 2019)

- Nancy A. Hewitt, No Permanent Waves: Recasting Histories of U.S. Feminism (Rutgers University Press, 2010)

- National Park Service, “19th Amendment” Series

- University of Washington History Department, “Woman Suffrage History & Geography, 1838-1920,” Mapping American Social Movements

- Academics

- Arts & Culture

- Diversity & Inclusion

- College of Arts & Sciences

- History

- Women's and Gender Studies

- Gonzaga Magazine