Finding Collaboration in West Africa

An excerpt from SEAS Dean Silliman’s concluding lecture to the First Year seminar, introducing new majors to the field of engineering.

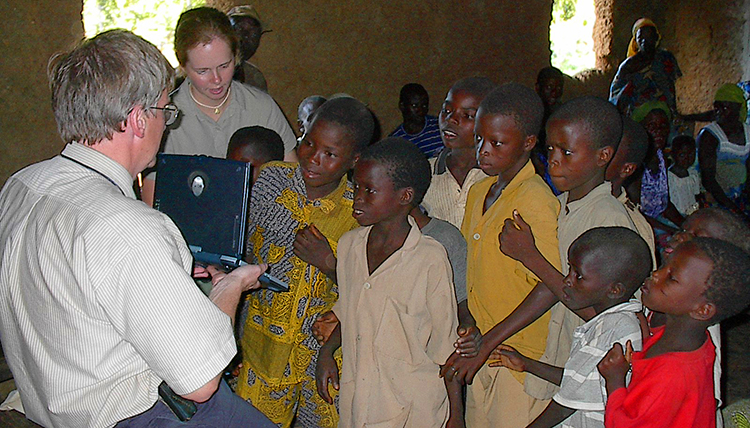

Engineering majors, think about this: Solar power remains only a small percentage of total electrical power production in the United States. But in those parts of rural Africa not connected to a power grid, solar power will make a 1,000-percent difference. There, you’re going from zero electricity to having the ability to recharge your cell phone or introduce a laptop computer into a rural primary school.

In the U.S., we rarely have a power outage – our lights remain on through most of our day. But if you sit at a student’s desk in Benin (West Africa), the lights are flickering all the time. If you want to kill a desktop computer, put it on a flickering power source without a surge protector, and it’ll be dead in about 30 minutes. So, as you consider possible impacts through your career, think about how developing a steady power source for a rural village would be an extraordinary application of engineering work in rural Africa.

In the United States, we talk a lot about MOOCs – the Massive Open Online Courses produced by Stanford, MIT and elsewhere. They are part of the answer to educating people in all parts of the world – all you need is the internet and computer, right? Well, if you’re in Nigeria, and you happen to be in Lagos, you probably have a pretty good chance of connecting to the internet. But if you travel 150 miles north of Lagos to rural Nigeria, how much internet is available there?

So, computer scientists and computer engineers, I dream about this. If we could get internet out into the rural villages – think of the difference we would make to the lives of children. But, there’s a caution here: This is Steve Silliman’s idea of what the African people need. Be careful! This is my idea, not theirs. In fact, one of the most moving lessons I learned in Benin was when we worked for about three years trying to improve education in the rural village of Adourekoman, Benin. Seventh-grade students involved in the project took an exam to see if they could go on to high school. Most failed the exam.

I was so depressed. But the parents came to us and said, “Thank you for your project.” It turns out that the luxury of sending their kids to go off to high school in another city could not be a high priority for these parents. You see, they are subsistence farmers, and they need labor to bring the crops in. If they lost half of those kids to high school, they would have lost a large part of their labor force. So, in actuality, just one very bright kid going on to high school was a great success for the village. They were happy for this child. It took me a long time to grasp that – their goal being so different from mine.

Successful projects in development often require long-term presence. I’ve spent summers in Benin since 1998 and by now I have close friends there – a few who have named a child for me or one of my students. In one village, their word for a white person is Pamela. Why? Because my student, Pamela, lived in their village every summer for several years.

In 2000, I went over to Benin with $10,000 and a small drill rig, and I drilled one well. I came back in 2003 with more money, and I drilled a second well. The first well is a perfectly good well, but for political reasons, it has never been used. Looking back, I see that I insisted on doing these two wells my way, trying to train a local population how to drill. But by 2004, a gentleman named Felix Azonsi, then the head of Benin’s water agency, knew me and trusted me enough that he could tell me I was using the wrong strategy.

I walked back in country at the end of 2004 with about $15,000 in my pocket and said, “Felix, I want to drill two more wells with my small drill rig.” He slapped me on the back of my head and asked, “Steve, how long are you going to be stupid?”

“It is time that you work with us, not independent of us. We’ve got better drill rigs here than you do – we also have trained drillers. We have a great drilling program in our country. It creates collaboration between the well program and the villagers, and requires villages to provide some of the money for the well as cost share – this gives them ownership of the well. What do you want to do? Do you want to continue to spend a lot of money to drill wells that may not work and that don’t address the national problem? Or do you want to use your money to work with us to help provide water to a lot of our people?”

That was a huge change point for me. I began to seek deeper input from my Benin colleagues on everything. Now that I’m a member of an international team, we’re actually getting some things done. Instead of me drilling two wells, the folks in Benin drilled 32 wells. Lesson learned: Trying to understand their culture and working with the government, the non-governmental organizations or NGOs, and with the local populations really makes a difference.

You can get involved in engineering and computer science overseas in a lot of different ways. You can do a two-week trip, or you can make a lifetime commitment. There are many ways to be involved that can be very valuable. Every engineering discipline can contribute in major ways. Further, this work provides opportunities to work closely with social scientists and leadership groups.

The challenge to us is to work with colleagues in the other country in order to find innovative engineering and computer science solutions to really tough problems that are acceptable to the people impacted by our projects.

I would argue that this kind of international work is extraordinarily consistent with a Jesuit and humanistic educational program – looking for God in everything around you.

SCHOOL OF ENGINEERING & APPLIED SCIENCE