Empathy: COVID-19's Silver Lining

Quarantine has had a motley mix of outcomes in terms of individual well-being. For the self-described introverts who received permission to avoid contact with others and stay home? Relief at last! For those already struggling with anxiety? Increased anxiousness. For socialites? Restlessness. Those responses were expected. But a positive and nearly universal response that may have the best impact on our collective well-being is the one shared by people who didn’t fit into those categories. The people who thought they were always balanced, in control, unshaken by change? Many of them had their first experiences with anxiety, panic attacks, fear of going out in public, or insatiable desires to curl up at home and hide from the world. All of a sudden, they felt empathy.

“If there was a tiny silver lining to COVID, it's giving people more opportunity to empathize with what it's like to feel this much anxiety. The feeling of being stuck at home may be new to some, but for others, it’s the norm of living with anxiety,” says Katie Noble, a health educator who oversees mental and emotional well-being and suicide prevention services in Gonzaga’s Office of Health Promotion. “Mental health is becoming a national conversation. People are ready to learn more.”

Noble had barely transitioned into her new role at Gonzaga before COVID-19 sent everyone home. During a normal school year, she and her colleagues provide community-based prevention training to students, faculty and staff. Together, they cover substance use, healthy relationships, and mental and emotional well-being, providing the tools for people to recognize signs that a student or colleague may be experiencing challenges from any of those three conditions or, more likely, a combination.

“We have to understand the intersectionality of those areas. A student in an unhealthy relationship may start drinking more. Someone’s mental health may be fractured due to an unhealthy relationship. A person with symptoms of depression may self-medicate with alcohol because they don't understand what's happening with their mental health. We can help put the pieces together,” says Noble.

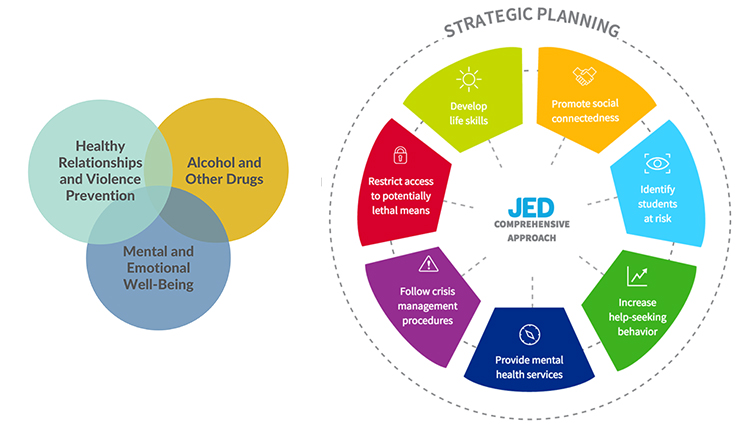

Left: The intersection of common challenges for college students.

Right: A systematic approach to prevention, created by The JED Foundation, which supports universities like Gonzaga in their suicide prevention efforts.

She provides trainings to help people have those conversations, and to decrease the stigma that often prevents a person from seeking help. In a normal campus environment, she would hold multiple in-person courses a month, including an eight-hour training called Mental Health First Aid. When COVID hit, she focused on the research being done in the moment to assess how college students were coping. In one survey of 2,000 students, 80% of respondents said the pandemic and related quarantine had impacted their mental health.

At the end of the spring semester, Noble shared related data in an email to Gonzaga faculty and staff. Her office also shared opportunities for virtual Mental Health First Aid training, which quickly resulted in more than 100 campus members signing up.

“They were recognizing and empathizing with students or others who may be in crisis and wanting to connect them to appropriate professional help,” Noble shares.

Working Together

Student Wellbeing and Healthy Living at Gonzaga has many “arms.” One is the Office of Health Promotion, which provides education and training to the campus as a whole. For individualized care, students access services through the Center for Cura Personalis and the Health & Counseling Center.

Talking About Suicide

Eleven-hundred students die to suicide every year in the U.S. Nationwide, 10% of college students say they have seriously considered suicide in the last year. Among Gonzaga students, that number was 14.3% in the most recent survey.

Noble offers a disclaimer: “The stats are difficult to pin down because of the reporting process, and there’s a national trend to change the way we report for better accuracy.”

But the margin of error is really not important. Any number of suicides is too many. Any attempt of suicide calls for better understanding.

The Mental Health First Aid training she provides at Gonzaga has been rewarding. One-hundred percent of participants have said they would recommend the course to others. Every training has had “light-bulb moments” where someone realizes that they really can support someone in a moment of crisis, as well as moments to demonstrate care before crisis occurs.

And there’s another reason those moments are gratifying.

“I’m a suicide attempt survivor,” Noble shares.

The reason I transitioned into mental health and suicide prevention is to step in for someone else the way another person did for me, and to allow others the permission to provide that support.

She understands that most of us would want to help a person giving thought to suicide, but we’re afraid to say the wrong thing. And she is quick to offer reassurance that, “Sometimes the smallest thing can make the biggest difference.”

She knows.

When she was a teen, sitting outside her high school, her band teacher was that big difference. He sat down next to her and said he recognized she was struggling. “You are not alone,” he said.

Today, Noble hopes that the empathy learned during COVID-19 will grow, and that more people will take the simple step to sit alongside another and utter those words: You are not alone.

“It’s such a critical component of how we support one another,” she says. “That's Jesuit. That’s caring for the whole person.”

Find Help

Gonzaga.edu – Health Promotion

Find a wellness toolkit, plus links to Collegiate Recovery Community, Zags Help Zags, and more.

Choose the RIGHT Counselor.

“Your counselor is just like every other relationship in your life. It's important to find someone you connect with and feel comfortable with,” says Noble.

>> Want to be Heard? Learn about the app by that name, developed by Gonzaga grad Andrew Riessen to match individuals with mental health providers who may be a good fit.

- Health & Wellness

- News Center